Back in 2011, a lot of amazing people helped me to celebrated the life of Jeff Krosnoff, the American IndyCar driver who was killed at the Molson Indy Toronto race on July 14, 1996. That six-part legacy series originally ran on the former SPEED.com site, and with the 20-year anniversary of Jeff’s death upon us, I’ve gone through and done a fresh edit on the Jeff Krosnoff: Stay Hungry series.

Start with Part 1 and follow with Part 2 below.

“A little more than a year ago, I was questioning the most effective way to give my career a boost. At that point, I was still working hard to land a ride in a formula car, but a drive was not going to materialize unless I came into a great personal fortune. I mean, my goal is to be [Formula 1] World Champion plain and simple, and how many F1 drivers have earned their big break in closed-wheel cars, let alone racing pickup trucks?”

~Jeff Krosnoff, On Track magazine, March 1989.

It would be like Ed Carpenter Racing’s Josef Newgarden, years before he won his 2011 Indy Lights championship, heading to Africa to achieve his dream of reaching the Indy 500.

That’s how crazy-risky it was for Krosnoff to leave America behind in 1989 to make a fresh start in Japan. The Japanese racing scene had become a viable option in the late eighties for a limited number of European drivers who’d run out of options in F3 or F3000, but it wasn’t even a consideration for an American with his eyes set on F1.

As unconventional as it might have been, Krosnoff was faced with a few harsh realities by the end of the 1988 season. One-year removed from battling in Formula Atlantics, he impressed everyone in the obscure SCCA Racetrucks series, but in terms of advancing his career, the stall was turning into a freefall.

The best times in Krosnoff’s young career had come while competing with his friends in the Jim Russell Racing School, the Mazda Pro Series, and again in the SCCA Pro Atlantic series. It was close and familiar at every stage, and as part of a wickedly talented group of young drivers vying for the big leagues, Krosnoff knew where he stood. Every race was a yardstick for the next generation, and he was among the elite.

That situation was lost in 1988 as his friends sped down paths to IndyCar or IMSA while he raced for Nissan in complete obscurity behind the wheel of a pickup truck.

Krosnoff and his wife Tracy were extremely close—she’d supported him throughout every false turn or dead end—but to get back in the game, Jeff realized extraordinary measures would be required. Shunned and forgotten in America, he craved the opportunity to rekindle his career somewhere…anywhere. Krosnoff also wanted a chance to race in an environment where friendship and camaraderie among racer–the kind he grew up with–still mattered.

That furtive, nurturing scene would be found, ironically, in the most foreign of lands.

“Throughout the past few years I had been developing a rather good relationship with a Japanese wheel company—Speed Star Wheels—and, in fact, had run its wheels on both my Atlantic car and Racetruck,” Krosnoff wrote in the same 1989 On Track issue.

“Anyway, towards the end of the ’87 season, I had been in Las Vegas for the SEMA show as part of the Speed Star exhibit. During the show, Mr. Asai, the director of the company, had been discussing with me the possibility of traveling to Japan to test in a Formula 3 car. Soon after that, Mr. Hamada, the owner of the company, said to come over and do a test in the Speed Star Racing Team’s Formula 3000 car!”

Krosnoff’s test actually came late in 1988 where he presented with the team’s year-old Lola. The test went well as he got to within two seconds of Masahiro Hasemi, Speed Star’s No. 1 driver at that time and a living legend in Japan. Frankly, the gap to the car’s regular driver should have been bigger. Crammed into a cockpit that was tailored to accept the much smaller Hasemi, Krosnoff impressed the team by finding speed while barely having enough room to shift gears.

He went home after the two-day test and soon got the call to join the team for the 1988 Japanese F3000 season finale at Suzuka in November. To acclimate himself with the 12-hour time change, and to get in some pre-event testing, Krosnoff’s trip would last 17 days, giving he and his wife the first taste of what his new career path could involve.

Qualifying 12th out of 22 cars, Krosnoff planned to draw from his experience doing standing starts in Atlantics, but without the opportunity to do a practice start with double the power in a 500-hp F3000 machine, he dropped the clutch when the lights turned green and hoped for the best. Krosnoff watched in horror as his car seemingly stood still, enveloped by a cloud of his own tire smoke while the rest of the field streaked away…

The NHRA-grade burnout looked spectacular, but Krosnoff dropped from 12th to 21st. In hindsight, the error turned out to be a blessing as the Speed Star team got to watch a great comeback drive where he made a number of thrilling passes to regain his original starting spot.

That fighting spirit, which Krosnoff possessed in copious amounts, was an intangible trait that was greatly valued in Japanese racing circles.

The march from to 12th to 21st and back to 12th would soon be halted by a delaminating rear tire, but the Speed Star owners had seen enough to offer Krosnoff a full-time drive for 1989.

With that move, Krosnoff joined a small but popular underclass of foreign drivers making a living in one (or more) of Japan’s four major series—F3, F3000, Japanese Touring Cars, and the All-Japan Sports Prototype Championship. The latter boasted healthy grids filled with factory Le Mans prototypes from Toyota and Nissan, along with semi-works entries from Jaguar and Porsche.

Japan’s economy was strong in 1989 and its three national series were awash with sponsorships and factory contracts on offer. Krosnoff made the move at the right time, and added Japanese touring car and prototype drives to a busy calendar, but like his switch to Racetrucks the year before, he was almost invisible to those racing at home and in Europe.

“I didn’t see him as much over there,” said Krosnoff’s childhood pal Tommy Kendall. “But he’d come home every now and then and I’d follow him as closely as I could, without the Internet being around for his first few years in Japan. News of his races were few and far between; I kept up mostly by reading On Track, but that always came out a few weeks after an event. He toiled away there kind of in obscurity but made some really deep impressions.”

Being gone for great lengths of time, as his friend and RACER Magazine founder Paul Pfanner shares, was a constant strain during Jeff’s seven-year stint in Japan.

“I remember there were times when he’d be home for a few weeks, but he’d be [in Japan] almost the entire time the season was active,” he said. “Once the season started, seeing him was infrequent. [His wife] Tracy would go over to Japan when she could, but the fact was Jeff was gone for long periods of time. It was hard on both of them. But the thing that he liked about it was that the guys he raced against were really good and it was a great benchmark and it helped establish his value. There was a standard that was maybe higher in Japan at the time.”

The sacrifices made in America by Jeff and Tracy Krosnoff to get his career to a point where they could reap the benefits went far beyond what the average driver and family is willing to endure. His move to Japan, in a different hemisphere, only compounded their stress, but his ability to remain locked on priorities helped manage the situation.

“The other drivers would want to go out and act young and crazy, but Jeff was married and was in a different place in his life,” Pfanner explained. “They’d try to drag him out to the bars, but he’d let them go and stay in his room to build a model F1 car, or something like that. He found that more fulfilling, which spoke a lot to the focus he maintained while he was there.”

Krosnoff’s life in Japan from 1989 through 1995 isn’t well documented—a testament to the obscurity Kendall referred to—but the education he received during the period was clear for all to see. Hidden away from the world’s motoring press, Krosnoff’s speed, skill and racecraft skyrocketed while simultaneously contesting two or three championships year after year.

Prior to Japan, he was getting by on raw talent in America while navigating the open-wheel ladder, and the responsibilities of life–from finding sponsorship, to attending university, to being a husband–made it hard to focus on his development as a driver. Krosnoff went as far as he could while also serving as a husband, student, and marketer, but compared to most of his West Coast contemporaries who lived relatively free and easy lives, Jeff was always preoccupied with grownup matters.

Once he landed in Japan for the 1989 season, and for the first time in his adult life, has was able to strip away the other daily responsibilities and invest all of his efforts into being a racecar driver. Krosnoff’s career went vertical in an instant.

The Japanese F3000 series, at that time, was unlike the rest of the national and international F3000 categories. With heavy funding and engineering resources dedicated by a number of Japanese tire manufacturers, Krosnoff and the rest of the drivers had an unbelievable scenario on their hands.

Compared to the control tires used in the other F3000 championships, Advan (Yokohama), Bridgestone, Dunlop and other brands spent fortunes on beating each other in Japan and it gave Krosnoff the chance to constantly test. With a championship that usually spanned March to November, Krosnoff was always in the car to try new rubber compounds, chassis and aero components, and anything else that might provide an advantage.

He was already known as one of the finer technical minds in the sport, but endless amounts of lapping and evaluating new bits further cemented his status as an elite development driver. In terms of mileage and personal growth, and after so many years of sporadic activity at home, Krosnoff was finally able to reach his full potential in Japan. He became hardened racer and a highly prized commodity, and with the boyish good looks working in his favor, the ‘California Kid’ was also a fan favorite.

Being away from home was never easy, but the cast of characters Krosnoff ran with in Japan provided plenty of distractions and amusement. He wasn’t the only American racing in F3000; Ross Cheever–younger brother of Indy 500 winner Eddie Cheever–was there, but during an era where the likes of Michael Schumacher, Jean Alesi, Eddie Irvine, Mauro Martini, Roland Ratzenberger, Jan Lammers and a host of other future stars competed in Japan, Krosnoff found a better fit among the European contingent.

As Kendall recalls, Krosnoff loved being one of the gaijins (the Japanese term for foreigners) and the tight-knit community of castaways and dreamers they formed.

“They all lived in this one hotel,” he said. “It was called the ‘Gaijin Racers Club…’ Or ‘Crub’ as Jeff would say it with the Japanese pronunciation of it in English. He was really close with [Mauro] Martini and [Eddie] Irvine. He would tell me about Irvine and the fun rivalry they had. Later–Eddie was already in F1, he heard Jeff got his IndyCar ride, so Irvine called to mess with him, and said something like, ‘Congratulations, but remember, you might be ‘mega star’ now, but I am a ‘giga star…’ They just had this razzing back and forth.

“It was similar to the camaraderie we had in the Russell Series of spending so much time together. It was the same with Roland Ratzenberger, who was a friend of his. He left Jeff’s outgoing message; he was Austrian so he had him do the Terminator voice. I’d call Jeff and get, ‘This is Jeff, I’ll be back,’ on his answering machine. It was clear they had a lot of fun over there, but Jeff was also clearly the adult in the room…”

Before he went on to drive for Jordan in Formula 1, Irvine, one of the sport’s most notorious playboys, recalled a great period in Japan where Krosnoff was a central character.

“I can’t even remember the first time we met, but he walked over to me and said ‘Hi’ at one of the tests at Suzuka,” the Irishman said. “Super friendly guy, typical kind of California guy, laid-back. In Europe everyone is kind of uptight in the racing circles, everyone is fighting for the few places that there are in Formula 1, and all the sort of exiles from Europe ended up in Japan. So when I went there everyone’s kind of looking at me like a new boy’s taken one of our possible drives. So it’s a little bit weird to start with. And Jeff was the first guy to come over and say ‘Hi’ to take that edge off and welcome me as a mate. And then we got on really well because obviously we were quite different. He was very sensible and enjoyed my wildness and I enjoyed his calmness. We even went on holiday to Guam together. I went mad and he watched the madness.”

Irvine says the time spent as a gaijin rates among his most treasured experiences in the sport.

“Well, to be honest, I stayed in Japan a lot, like Jeff,” he continued. “Jeff had a wife to look after and he was trying to put away as much money as he could, as I was, because in motor racing you never know when the money’s going to stop coming, so I was super cautious and Jeff was reasonably cautious as well. It was a lovely time. I remember it really affectionately. Like, if I didn’t get to Formula 1, I would’ve been happy staying in Japan. We had great racing, we were earning really good money and I had a great life. It was a much more friendly set-up.

“Once you got in, once you were in the gang, we all went out and had a really good time. Tokyo is a big place but was very small for us because we all went to the same sort of five places. So it was a really wonderful time, I have to say, compared to Formula 1, which, okay, you’ve got the fame and the money and the most amazing cars and all that sort of stuff; you didn’t have the camaraderie that we had out there in Japan, which was something. Looking back, you need a lot more than the other stuff. The other stuff will disappear. That won’t.”

Irvine and Krosnoff became elder statesman among the gaijins, and as 8-time Le Mans winner Tom Kristensen shares, the friendly Californian went out of his way to welcome the young Dane to Japan.

“I was a little bit younger, from the Formula 3 generation, if you call it that, and Jeff was the Formula 3000 generation,” Kristensen said. “I remember him as always very open, and you could always ask him about stuff. He was always friendly, he was very natural – a very positive man. Sometimes we went to restaurants in Tokyo together but it was normally, we would be like four or six people.

“And to have success in Japan with a different culture is, for me, you need to be a humble person with a passion for what you’re doing. Sometimes in Formula 3000 he didn’t have the best material, maybe he had one tire and the other tire company was the one to use that year, but he loved what he was doing and he wanted one day to go back to America and to prove himself. I think for an American to go via Japan, that’s not really a normal way and I think a lot of people respected him for that.”

Krosnoff’s sports car career was also flourishing in Japan, although racing in the equivalent of today’s Super GT category, and the Sports Prototype championship, was not his central focus.

His first taste of proper sports car racing came as a member of a satellite factory team, TWR Suntec Jaguar. Piloting a variety of turbocharged, V8- and V12-powered prototypes for the heiress to the Suntory Brewery fortune, Krosnoff made a strong impression on TWR team manager Tony Dowe.

“He was selected by Mrs. Yamazaki from Suntory because he was quite a big name in Japan,” Dowe said. “He knew all the Japanese tracks and although it wasn’t a high priority program for us—we had full-blown efforts in IMSA and the World Sports Car Championship–Jeff did a really good job. Our engine shop was into the Japanese series because it was all but unrestricted there. We sent them a qualifying engine once—it was going to be a basket case after two laps—but Jeff did a great job with it, just wore it out.

“He was on the road to becoming a TWR driver, I believe. He would call me when he would pop back to America, wanting to do IMSA with us. When we started that [GTP] program [in 1988], we had to work through all the promises we’d made to all kinds of drivers, so they got the first drives, but we were getting to a point where there wasn’t going to be an impediment for Jeff to drive for us.”

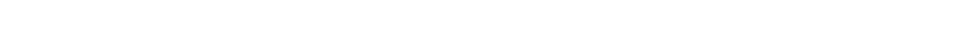

After many years of local success in Japan, Krosnoff would write his name on the world stage for the first time in 1994. Teamed with Irvine and Mauro Martini in a factory Toyota 94C-V, Krosnoff and his F3000 friends nearly won the 24 Hours of Le Mans on their first attempt for the Japanese brand.

“Well, to be honest, we were leading it and we would’ve won it,” Irvine said with absolute assuredness. “We were leading it by a mile and we would’ve won it and Jeff had that problem with the screw coming out of the gear lever at the back of the gearbox. He had the wherewithal to get out of the car, get underneath it and jam it in gear. And the bad luck of it was he was stuck in first or second gear so we had to do the next lap, obviously, very, very slowly.

“If we had had some luck and it jammed in third or fourth or fifth or something, we could have probably still won; but I thought it was one of the best races in my life, from a personal point of view. It was one of the most pleasurable races in my life because I was doing Le Mans with two good friends.”

With most of the racing world watching as Krosnoff lost the lead with 90 minutes left to run, the eventual return to the pits for repairs and handover to Irvine would soon deliver an epic comeback performance that netted second overall and first in the GTP class.

“I overtook one of the [two] factory Porsches in the last corner in the last lap for second,” Irvine added. “That was one of the best highlights of my career, to be honest, that last stint. It was absolute madness because of all the cars going slowly and the Porsches and me, it was just basically me and two Porsches racing because for everyone else the race was over pretty much.

“We had a really good time and, again, it was the camaraderie thing where it’s us three against the rest, up on the podium looking out on a sea of people and laughing about what we’d achieved. Jeff did a great job. He was super consistent, fast, and made no mistakes.”

Of the three teammates, Krosnoff’s value spiked after Le Mans, while Irvine–already in F1–earned more praise for nearly stealing the race back from Porsche.

As Krosnoff would find upon his return to Japan, the speed and consistency displayed in France started to attract interest in his services elsewhere in the world. One more year of F3000 and sports cars beckoned in 1995, but as Kendall recalls, Krosnoff’s unwavering belief that racing in Japan would lead to bigger opportunities was coming closer to reality.

“Well, when Jeff went to Japan, the analogy was like it was a huge pit and all these drivers are down it and it’s just sheer granite walls and there is no way out,” he said. “If you’ve got the money, they helicopter you out of there. But most people in there eventually give up and say, ‘Well, I can’t do it.’ And Jeff was the one crazy guy who said, ‘No, I’m going to climb that wall and get out.’ It’s literally no toe-holds, no foot-holds, and everybody’s like, ‘There’s no way you can climb that wall.’ That was what he faced. He was being told constantly: Japan is not the way out; you can’t get out that way. He had to go off of pure determination and to hold onto every little thing he could.

“He went that way even though there was no light at the end of the tunnel, and he’s just said, ‘I’m not going to stop. I’m just going to go wherever this leads me.’ The top European guys got out of Japan because there was always a market for them, but as an American? There just wasn’t a market for a guy like Jeff in the eyes of F1 teams. He was a curiosity. After Michael [Andretti] came home from F1 [in 1993] after things went badly with McLaren, an American wouldn’t even be considered.

“And, like I said, there was this confidence about him that emanated from him that he was going to make it somehow, some way. And so, it finally came around full circle. It just wasn’t the invite to F1 he’d spent all those years chasing after.”

By the time he was 31, Krosnoff had already spent most of his twenties racing professionally in Japan, and it’s fair to say his age was becoming a limitation.

He’d finished as high as second in the F3000 championship, but with 1996 drawing closer, and as Krosnoff saw from afar, a strong crop of young drivers in their early twenties were on the move at home.

A promising Canadian by the name of Greg Moore, who had risen up America’s open-wheel ranks in Krosnoff’s absence, would be making his debut in CART in ‘96. Tony Kanaan, fresh out of Italian F3, and Helio Castro Neves, a graduate of the British F3 series, were pointed towards America to try and earn the Firestone Indy Lights crown that same year.

Scotland’s Dario Franchitti was also on the horizon, and whether it was happening in ‘96 or in the years to come, it seemed like most of the open-wheel talent outside of F1 was destined for a seat in IndyCar racing. A particular 31-year-old American, stuck in Japan, was beginning to wonder if he’d have a seat of his own back home, and fortunately, one of his old acquaintances was asking the same question.

“You know, I just really enjoyed Jeff Krosnoff as a person, separate from what he was able to do on the racetrack,” said Chip Ganassi Racing managing director Mike Hull. “We were both from southern California, and we developed a relationship with each other over time. He was racing Formula Mazda when I first met him, and we kept in contact. Then when he continued to race and he wasn’t able to find a drive in the United States, so he went to Japan and raced and we kept in contact as much as we could while I was working in CART.

“At the end of ’95, [Chip Ganassi] wanted to make some driver changes here and he came to [his management and engineering team of] Tom Anderson, myself and Morris Nunn. He called and said, ‘I’d like to come down to Indianapolis and sit down with you guys and talk about having a driver test to determine who can drive as a teammate with Jimmy Vasser in 1996.’

“And so Chip came to the building and Tom, Morris and myself sat down, and Chip said, ‘I want to have a driver test, you guys determine where we can do an oval and road course test, where it makes the most practical sense, and set the schedule. I have somebody I would like you to test. He comes recommended from Adrian Reynard and Rick Gorne. His name is Alex Zanardi. Now, if any of you sitting here want to have somebody also, we’d like to have a comparative test, so if there’s anyone any of you would like to have, speak up or let me know who you’d like it to be and make arrangements and get that person there so we can have a proper comparative test.’”

They’d only seen each other on rare occasions during his long adventure in Japan, but Krosnoff had made enough of an impression on Hull that when it came time to propose a candidate to replace Bryan Herta in one of the most promising seats in CART, a certain name stood out above the rest.

“So Morris had a choice–Norberto Fontana, who was racing in Europe in Formula 3000, and Tom chose not to join in on putting a name in the hat,” Hull said. “So we tried to get Fontana to test but he had a Formula 1 testing contract and they wouldn’t allow him to come over. So it was down to me and I contacted Jeff, who was still in Japan, and I made arrangements for him to come and be part of that test evaluation process. We organized ourselves to go to Homestead so we could go on both the road track and on the oval. This was going to be a proper shootout.”

Prior to Hull’s unexpected outreach from America, and after so many years of watching fellow gaijins arrive, succeeded, and leave Japan for greener pastures, Krosnoff was beginning to wonder if his best days in the sport were in the past.

“Contemporary motorsports is a difficult business, and as hard as I worked to reach F1 or Indy cars, nothing was happening,” he wrote in his final submission to RACER Magazine. “It was especially hard to take at various times and so, near the end of [1995], I was having to come to terms with the fact that my career might not ever reach the lofty expectations I envisioned for myself as a snot-nosed youngster.”

Doubts aside, and thanks to the continual encouragement from his wife and an old friend with leverage in the Ganassi camp, Krosnoff was about to make the journey home.

Seven years of heavy sacrifice was about to pay off, and his life would never be the same.

Coming up in Part 3: A shot to make it in America.