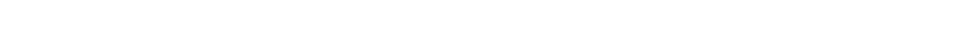

Back in 2011, a lot of amazing people helped me to celebrated the life of Jeff Krosnoff, the American IndyCar driver who was killed at the Molson Indy Toronto race on July 14, 1996. That six-part legacy series originally ran on FOX’s former SPEED.com site, and with the 20-year anniversary of Jeff’s death upon us, I’ve gone through and done a fresh edit on the Jeff Krosnoff: Stay Hungry series, starting with Part 1 below.

“What was Jeff’s legacy in this sport? Me. I am his legacy. He touched so many lives, including mine. When my kid grows up and looks at pictures of me driving Jeff’s car after he died, I’ll tell him, ‘Poppy was able to continue the dream of this man like I continue the dream of my father, and then you will continue my dreams one day.’ That’s how I look at what Jeff did to someone like me.”

~Max Papis

It’s a phrase that gets used far too often, but I do remember the crash that killed Jeff Krosnoff like it was yesterday. All I have to do is close my eyes and I’m transported back to where I was standing on that haunting day in the Toronto paddock when Krosnoff’s life ended with jarring speed and violence.

Dammit. This can’t be happening. Not Jeff. Not now. F**k. He didn’t get the chance to show us what he could do.

The day of Krosnoff’s death was instantly seared into my memory. I’ve mourned the loss of many drivers—personal heroes like Ayrton Senna and Al Holbert—but Krosnoff’s death struck in a different way. Krosnoff, a 31-year-old rookie in the CART IndyCar Series, got his first shot in the big leagues in 1996, but tragically, that rookie season lasted just five months.

Being cut down before he could take IndyCar by storm felt cruel and personal. Sadder still was the fact that his fatal accident also claimed the life of corner worker Gary Avrin. Two bright lights, extinguished in an instant.

20 years later, and with the Oklahoma-born, California-bred Krosnoff somewhat of a mystery to many of today’s open-wheel fans, the magnitude of his loss is hard to shape and contextualize without straying into nostalgia.

He was an Indy car driver for 11 rounds and never came close to winning, but to define his legacy from a half-season in CART would be incredibly short-sighted. Krosnoff was a beacon to many—living proof that obstacles could be overcome with talent and determination. He was ignored, turned down and cast aside more often than not, yet refused to complain or accept defeat. He took control of his destiny and went to extraordinary measures, including leaving his wife and family behind to compete halfway around the world in pursuit of his dream.

He drove for major factories like Toyota, Nissan and Jaguar, had a cult following that included fellow drivers and his closest rivals before earning a seat in IndyCar, but was largely unknown when he returned home.

A musician, photographer, writer, motivator and friend, Krosnoff was so much more than a driver of racing cars. With the help of those who knew him, plus some of his own writings, the remarkable life and journey of Jeff Krosnoff can be celebrated in the manner this massively influential character deserves.

“The earliest memory I have about wanting to be a race car driver was while I was in kindergarten,” Krosnoff wrote in an issue of RACER Magazine. “It was a bright and sunny day at La Canāda Elementary School, and one of my favorite activities was scheduled. Not only were ‘Sloppy Joes’ on the cafeteria menu, but it was ‘Show and Tell’ for our class. On this particular day, I remember a little blonde girl brought in something quite unusual to show our class. It was a trophy her father had won.

“To describe it is like trying to colorize classic movies—almost impossible and never quite accurate. Atop the white marble base sat a most brilliant golden likeness of a race car. When it was my turn to hold it, I didn’t—or couldn’t—let go. I spent the rest of the day staring at it on her desk from my seat across the room. It was then that my dream began. A dream that I pursue to this day… that girl’s name was Kathy Bucknum. Her father was Ronnie Bucknum, one of the first Honda Formula 1 pilots…”

Krosnoff grew up in a southern California at a time when the Golden State—and the West Coast in general—was a hotbed for driving talent. Jimmy Vasser, Mike and Robbie Groff, Steve and Cary Bren, Mark and Mike Smith, Tommy and Bart Kendall, and many others took the same path as Krosnoff. Collectively, they made their way from various grade schools to local road courses in record time.

“Jeff lived about a mile from me in La Canāda and I think I probably met him when I was about nine or 10,” said Tommy Kendall, whose open-wheel career mirrored Krosnoff’s early in the early days.

“Our parents were friends. We went to different schools but I knew him–he was two years older than me and he got a go-kart before anybody else I knew. I remember seeing him drive it at his house and I couldn’t believe it, because it wasn’t the little put-put karts that I’d tried. He was ripping around his driveway and I’d never seen anything like it. I was into dirt bikes before that, but that’s the first time I had seen the real deal with four wheels. So fast forward a little bit to when I’m driving, and I started in karts and then went to the Jim Russell Racing Series.

“Back then, that was the only place you could really race before you were 18, and Jeff was already doing that. He was the guy that taught me what it meant to be serious about racing. He was in unbelievable shape. He never, I think in his life, had a sip of alcohol. He was the guy I looked up the most to and spent the most time with. I had a first-hand look at how he was preparing and I didn’t know if anyone was preparing more than that, but it really gave me a lot to think about.”

Krosnoff’s trek up the 1980s version of the open-wheel ladder included his aforementioned start at Jim Russell in 1983, where seven wins in the school’s aged Van Diemen RF78 Formula Fords signaled great promise.

He’d stay in the Russell family for 1984 as part of the inaugural Mazda Pro Series—what is now known as Pro Mazda—and finished second in the championship. Selected to On Track magazine’s “America’s Choice” roster for his impressive pro racing debut in ’84, Steve Nickless’ entry for Krosnoff was succinct: “A teenager with boundless potential.”

While at Russell, Krosnoff would meet Paul Pfanner and an immense bond was immediately formed. Pfanner, who would go on to found RACER, followed Krosnoff’s career from the beginning thanks to Nickless.

“Steve had been the founding editor and creator of On Track magazine,” Pfanner said. “I worked with Steve years before and we were working with the Jim Russell people to produce their newsletter and help them with their marketing. Steve was doing the editing of the Russell newsletter and he had seen Jeff race in some of the Russell Series races down in Riverside.

“When I started to hear how quick Jeff was, I became interested in his progress straightaway. He was very quick and I then got to watch him race and I was very impressed. Clean, precise, just looked like he was inevitable. And it was a pretty big feat with the people coming through at the time but he was a standout to me. We got to know each other. I just liked his personality. He was very funny. We were just wild pups but it makes me smile just to think of it.”

Krosnoff’s parents were successful, but when it came to auto racing—especially making a serious career out of driving racecars—Pfanner says his friend, in what would become a defining aspect of his personality, accepted responsibility for making his own way in the sport.

“What got me about it was his complete self-reliance in finding money and putting deals together and dogged persistence,” he said. “Just the self-confidence to basically go after opportunities, to wait outside an office, make sure he got paid attention to while he was getting his results early on.

“He just was going to find a way and he wasn’t waiting for someone to write a check for him. He was self-reliant and reciprocal as well. So a lot of people had talent and they would just let the talent speak for itself. That wasn’t Jeff.”

Another element of Krosnoff’s character stood out while Pfanner was getting to know the young racer.

“He also had a sense of humor,” he said. “I recall on his very first Formula Russell Mazda car, he put together all this money from bits and scraps and pieces from friends and he wanted to put a logo on the car, so in very large letters he just had the phrase ‘underworld coverup’ as the sponsor on the car. People obviously asked questions, which is what he was after; it engaged them in a conversation.”

With the West Coast-based Jim Russell/Mazda Pro Series growing in size and prominence, Krosnoff continued to cut his teeth in the category in 1985 and 1986 where he earned three wins. He’d also add a round of the SCCA Westpro Sports 2000 Series to his calendar as an introduction to sports car competition

To complicate matters, Krosnoff was climbing his way up the racing ladder while pursuing higher education.

“25-year-old UCLA psychology student Jeff Krosnoff’s victory at Tacoma was particularly noteworthy in that it came in his very first Sports 2000 start,” Bill Lorenzen wrote in his 1986 Pro Sports 2000 Season Review for On Track. “Krosnoff never put a foot wrong in a most impressive display with a Brisken Racing Swift DB-2.”

In a touch of subtlety, Lorenzen left out the fact that Krosnoff also earned pole position on his sports car debut.

Back in his full-time program, Krosnoff ended 1986 as a star on the rise while battling eventual Mazda Pro Series champion Jon Beekhuis, Mark Wolocatiuk, Johnny O’Connell and other respected drivers, but missing out on the title proved costly.

While he said nothing of the situation publically, Krosnoff’s run at the title was complicated by his crew chief, Clayton Bierke, who was caught making illegal modifications to his driver’s Mazda 13B engine on two separate occasions. Krosnoff was disqualified both times, forfeiting the win and points at the final round of the championship.

The season that should have been a springboard to catch the eye of big SCCA Formula Atlantic teams ended in disarray. With limited funds at his disposal, and his senior year at UCLA beckoning in 1987, Krosnoff’s young career was at a crossroads.

As a classic glass-half-full type, he was brimming with enthusiasm before the start of the 1987 Atlantic series season, but without the name or sponsorship to land a front-running seat, options were limited. Even with the best drives taken by his rivals, Krosnoff hoped his first taste of big power, bigger tires and serious downforce would set him in motion to arrive at his ultimate destination: Formula 1.

“I have always liked Atlantic and I am extremely excited to be involved in the series this year,” he said in earlier writings that were published by RACER Magazine. “I feel it’s the best experience-gaining series around, and I look forward to learning and competing. For me, this is a dream come true. Formula 1 has always been my goal and I now feel I am on the right path with the right people.”

That pre-season optimism was routinely tested as he went winless in ‘87, finishing sixth in the championship while driving an outdated Ralt RT-4/85 while most of the top drivers like Beekhuis, O’Connell, Parker Johnstone, Ted Prappas and eventual champion Dean Hall had ’86 or ’87 Ralts at their disposal.

From 1983 to 1987, Krosnoff had shown great promise, earned respect, and overcame a variety of obstacles, but in an era where a dozen or more drivers with similar stories were produced in Formula Ford, Pro Mazda, Super Vee and Atlantics, Krosnoff found himself left out from On Track’s “America’s Choice” conversation. Whatever momentum he’d established was about to come crashing down.

Hailed as one of the biggest drops in an upcoming driver’s career at the time, Krosnoff went from SCCA’s top open-wheel series in 1987 to its newest and most ridiculed championship for 1988, the Coors Racetruck Challenge.

It boasted factory programs from Ford, Dodge, Jeep, Mitsubishi and Nissan, but the comical Racetruck series, comprised of damn near stock mini-pickup trucks, is where Krosnoff was left to ply his trade with Nissan while his friends drew closer to realizing their dreams.

“He basically just went wherever the opportunities took him,” Kendall said. “He ran out of funding pretty quickly at the open-wheel side of things. He begged and borrowed to do Atlantics. I remember getting a little grief from Jeff when I had had a similar situation where I really wanted to be an open-wheel racer but once you got past the Mazda Pro Series the next step was Super Vee or Atlantics, and that was $250-400 grand a year. That just wasn’t going to happen. If you couldn’t afford that top-dollar program, you were going nowhere.

“And then when he got the test in Racetrucks for the Nissan team–I think they did the test at Carlsbad Raceway or something like that—and I remember hearing that he actually crashed the thing. He’d never raced anything silly like that… I don’t think he crashed it badly, but he crashed it, but he was also the fastest by a decent margin, and so he got the nod.”

Krosnoff would return to the win column with four victories and claimed second in the Racetrucks championship, but dropping off the open-wheel radar all but ended his forward progress in America.

Like Krosnoff, Kendall had been forced into an unexpected direction due to budget constraints, although his transition—from open-wheel to the IMSA GTU series in a Mazda RX-7—came a few years before Krosnoff was relegated to the Racetrucks series.

“I did some IMSA races in ’85 alongside my Russell program, about four of them,” Kendall said. “I remember getting some grief from Jeff and from some of the other open-wheel guys saying, ‘Why do you want to do that?’ I told them, ‘It’s not really what I want to do; it’s the only thing I can do.’ I think Jeff got a better feeling for the choice I had to make when he went from Atlantic to the trucks…”

As his closest pals were racing in Atlantics, the American Racing Series (precursor to today’s Indy Lights Series), and IMSA, Krosnoff kept his spirits high and managed to find fun and humor in being the planet’s most overqualified Racetruck driver.

“I can’t quite remember what the occasion was, but I made a remark about how slow the SCCA race trucks were,” Pfanner said. “And we always exchanged photographs and pictures with each other. So I said if he was a real man he would actually take photographs while he was racing. And he laughs and we joked about it. And probably two weeks later in the mail I received an envelope with these photographs and they were hilarious.

“He literally, the entire race–and I don’t think the stewards would’ve been happy about it–documented the race with his camera in one hand, all the passes he made… There was a flash shot I think looking over at Steve Saleen’s truck and you could see the surprise that the flash was going off in Saleen’s face. He did get a picture of him taking the win. Crossing the finish line in first place.

“The whole thing was documented in sequence, so he took the dare. And I think the other thing that was fun about that camera was it went everywhere with him and captured all sorts of mischief. Not the least of which occasionally, we’d head to the bathroom when we were out with the guys and he’d just put that camera over the top of the stall and would randomly catch someone, just shoot a shot, just for the hell of it, and later it would be fun to see what he got. He was just mischievous. He was just a wild pup.”

Running well out of the racing spotlight didn’t faze Krosnoff. To his peers, he’d taken a few dozen steps back, but Krosnoff’s faith would eventually be rewarded.

“Shortly after when I got on with Mazda in a full factory IMSA program,” Kendall recalled, “I think the light went on for Jeff. It was a way to keep racing and actually maybe even advance himself because the Japanese car companies were starting to get heavy into racing in Japan and also in America. Truthfully, driving for Nissan in Racetrucks was a far cry from Atlantics in terms of enjoyment, stimulation, and challenge.

“It was a huge step down, but he was smart enough to figure out that maybe it wasn’t a direct route to where he was going, but it was a route that actually had a chance of somebody else paying for his journey. Most guys were fighting to get money from a regular sponsor, but Jeff saw the logic in becoming a factory driver at a pretty early stage. Open-wheel guys just weren’t doing that back then. It was a very original idea.”

In another piece published by RACER, Krosnoff tipped his hand at why the shocking move to Racetrucks wasn’t triggering panic attacks.

“First, I am a formula driver in the purest sense of the word,” he said. “Despite my gunsight training with formula cars, I do not feel that I am going backward by running Racetrucks. To the contrary, I feel it is a positive step forward because what these little rigs lack in horsepower they make up in corporate support.”

Humbling himself in 1988—looking farther down the road than most young drivers can see—paid off in the most unexpected manner.

“Jeff would just about do anything to get in a racecar and he would go to the auto industry trade shows, he would walk around and meet people,” Pfanner said. “That’s where he met the people from the [Speed Star/5Zigen] wheel company that eventually brought him to Japan. As improbable as it seems, from racing in that SCCA pickup truck series, he met people who hired him to drive Formula Nippon and Group C cars and Super GT cars as a result of just a grand bluff of self-confidence and ability. You just don’t see that happen very often anymore.”

From falling out of favor in 1987 to falling off the map in 1988, Krosnoff was about to orchestrate one of racing’s great career turnarounds.

Coming up in Part 2: Jeff makes a massive gamble.