Originally posted in May, 2011.

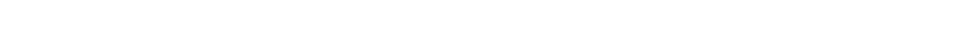

We left you after Part 1 of Willy T. Ribbs: One Of A Kind with Ribbs at an all-time low after failing to get through the Rookie Orientation Program for the 1985 Indy 500. In Part 2, Ribbs meets the man who would rekindle a lost dream, and in doing so, help make history at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

“DON’T DAMAGE ME”

After returning to his role as one of America’s premier sports car drivers, Willy T. Ribbs spent the rest of 1985 attempting to repair his image. With wounds still fresh from the mini-disaster at the Indy 500 ROP, Ribbs went about healing himself by dominating the second half of the SCCA Trans-Am championship.

Five wins from June to November for Jack Roush and Ford served as a reminder Ribbs’ capabilities in equally-prepared machinery. While he lost out on the championship by 15 points to his teammate Wally Dallenbach Jr., Ribbs’ career was once again on the upswing.

A test in December of 1985 for the Brabham F1 team earned Ribbs the distinction of becoming the first African-American driver to pilot F1 machinery, but with unfinished business at Indy, the test was little more than an interesting footnote.

A switch to Chevrolet and the IMSA GTO series for 1986 saw Ribbs add a few more wins to his record, but the call from Dan Gurney to join All American Racers’ Toyota GTO program for 1987 is where Ribbs’ road to Indy gained the most traction.

Six stylish wins for AAR through 1987 and 1988 made a lot of headlines, and it was during one of those wins—at his home track in Northern California—where Ribbs’ second Indy chance sparked to life.

“I won a race at Sears Point in 1988 and as it turns out, Bill Cosby was in town in San Francisco,” Ribbs said. “I used to do the ‘Ali Shuffle’ on the roof of the car when I won, and they went with that clip on the sports shows. I remember Sports Nation had that on the Sunday night news, and I guess Cosby saw me and heard I was winning a bunch of races and wanted to reach out to me.

“So I got a call from one of his people and he asked me to come meet him in his hotel room. I’ll never forget it. We got to talking, and this is Bill Cosby, right? The most popular entertainer in America. The number one TV show in America, right? So he asks me, ‘I don’t know anything about racing, but what do you want to do? What’s your goal?’

“I told him IndyCar racing is where I wanted to be. So he asked me what it cost to go IndyCar racing, I told him…he takes a loooong pause, and says, ‘OK, let’s do it…but don’t tell my wife…she’ll kill me…’”

Cosby also left Ribbs with a parting message which set the tone for their working relationship.

“I remember Bill had one of his cigars in his mouth,” he continued. “He took a pull on it, looked me in the eye, and said, ‘Don’t damage me.’ And I knew exactly what he meant. He didn’t have to say another word. There were so many athletes back then getting into to trouble and embarrassing their teams or sponsors or whatever, and Cos’ was as high-profile as you could get. The most beloved guy in America. A father-figure to everyone, white and black. He was going out on a limb for me—a guy he just met. The last thing he needed was for his reputation to be tarnished, and I wasn’t going to let that happen.”

NO THANK YOU

As Cosby spent more researching the economics of IndyCar racing, Ribbs says the entertainer was drawn to the example set by Paul Newman, co-owner of Newman/Haas Racing IndyCar program. Cosby’s unhurried review of Newman’s financial approach meant the partnership with Ribbs took 18 months to reach the racetrack.

“Cosby wanted to help me, but he was a smart businessman,” Ribbs explained. “He said he wanted to do it like Newman, who used his connections to fund the team. Newman’s name brought sponsors in, and Bill saw that as the way to go for him. He was smart that way, and figured that as the spokesman for a bunch of big companies back then, his agents would be able to find the money—and it wasn’t a lot of money we needed—to go IndyCar racing. But it didn’t happen. It just didn’t happen.”

Ribbs’ benefactor agreed with his assessment.

“The main thing is, Mrs. Cosby and I…for Willy, this was a donation,” Cosby said. “This racecar thing is a business. I was not ready to shut down my business to go into a business, mainly because I’m hoping for that which a Paul Newman would get. We put something in and it was up and running, and we hoped that this is something sponsors in America wanted to support. And it just was way beyond my knowledge. I knew nothing about it. The only thing I knew was I wrote a check and then I allowed the people to see Bill Cosby backing Willy T. Ribbs, okay? So now we were ready for anybody who wanted to join. We’ve got a good group of people ready to run Willy, ready to go…and we just kept getting negatives. Negatives.”

Those negatives became something Ribbs took very personally–then and now.

“No one wanted to support what we were doing, and I’ll be honest…it was the most hurtful thing I experienced in IndyCar,” he said. “I’m thinking, ‘If they won’t sponsor me with Bill attached, I must really not be wanted in IndyCar.’ They searched in 1988 and in 1989 and nothing. No money. Finally, Bill got so fed up, he said, ‘Enough. I’m going to put up my own money to get this started.’ And then we did the deal with the Raynor [IndyCar] team in 1990.”

JEAN PATRICK HEIN

Ribbs showed potential competing in eight road course events on the 16-race calendar with the Ray Neisewander Jr.-owned, Kim Green-led Raynor-Cosby team, but other than a 10th at Vancouver, his rookie season produced limited results.

The events that took place during the inaugural Molson Indy Vancouver race would also galvanize Ribbs in a way he could not have anticipated.

Ribbs’ 10th-place result, while impressive, was marred by the death of 20-year-old corner worker Jean Patrick Hein. Hein, along with three other corner workers, were tending to the stalled car of IndyCar rookie Ross Bentley on the opposite side of a blind chicane, and after bump-starting Bentley’s Lola-Cosworth, the workers sprinted across the track to seek protection behind the marshal’s post.

All three failed to look to their right for oncoming cars before they started to move, and with Ribbs as the first driver on the scene without their knowledge, contact was made. Two workers bounced off Ribbs’ left rear tire and the left endplate on his rear wing while Hein, unaware he was running into traffic, went under Ribbs’ left rear wheel and succumbed to the violent head trauma suffered in the accident.

Ribbs was later exonerated in the official investigation, but the event weighed heavily on him and the team. After one more race in his abbreviated season, Ribbs’ rookie season was finished, along with the Raynor-Cosby partnership.

Although the Raynor team was respected in the CART paddock as a dedicated group of hard workers, the program was on the decline when Ribbs arrived in 1990. With the relatively unloved Judd engine powering a year-old Lola chassis, Ribbs was never going to feature against teams with brand-new cars and more powerful motors. Despite all of the caveats, the fact remained that Ribbs failed to impress at most races and made a fair amount of contact while learning the ropes.

Ribbs clearly had potential, but Cosby’s agents didn’t have much to show or impress potential sponsors at the conclusion of 1990.

WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE?

With Neisewander shutting down the Raynor team at the end of the season, Ribbs went into 1991 without an IndyCar ride and was left wondering if another return to sports car racing was the best move to feed his family.

Like Ribbs, Cosby’s first experience in IndyCar wasn’t entirely positive. Although he put up his own money to place Ribbs in the Raynor car, his presence in the sport did not translate into corporate support. Just as his driver struggled to grasp their lack of on-track success, the country’s most famous star was shaken by the indifference he received in boardrooms throughout America. The sporting marriage of Cosby and Ribbs, for all of its potential, was a box office failure.

Their sponsorship drought continued during the off-season, and into 1991, where Ribbs sat out the first three IndyCar races. In a repeat of the situation that led to the funding of Ribbs’ ride at Raynor, Cosby grew frustrated and dug into his pocket once more to support his driver. Unlike their first deal, the 1991 arrangement involved with a comparatively modest sum of money.

All Cosby and Ribbs needed to find was a willing team interested in fielding a car on tight budget.

FANCY MEETING YOU HERE

“I had just finished the year before with the IndyCar program for Porsche and they had got disenchanted by what was happening in IndyCar racing at that time,” said veteran team owner Derrick Walker. “And so they said, ‘sell everything we’ve got here. Send the cars and the engines back to Germany and sell everything off. And I ambitiously thought this was my chance. So I said, ‘I’ll take it and I’ll start my own race team.’”

Walker, the respected ex-Penske Racing team manager who moved over to lead Porsche’s factory IndyCar program in the wake of Al Holbert’s death in 1988, seized the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

Owning the equipment to go racing, as Walker shares, was only half of the equation.

“I had no means to be able to do that but somehow it seemed like a good idea at the time,” he continued. “So I ended up with all of this stuff and Porsche was really helpful in giving me enough time to bury myself in it. And so going into the New Year, I was a team owner with a bunch of stuff that I really didn’t own yet and I was walking around with my tongue hanging out trying to figure out how I was actually going to start my race team. And then I bumped into Willy T. Ribbs.

“I knew who he was but he didn’t know me that well or vice versa, but I bumped into him and in the course of the conversation he told me that he had a little bit of money from Bill Cosby and was going to try and run Indy and could we run Indy with him? Could we put a car in the race for Indy? So that’s how it started.”

“HE LOOKED LIKE RINGO STARR”

Of the many things Ribbs learned from his brutal Indy 1985 experience, having a motivated and experienced crew was going to be essential. He knew Walker by reputation, and as more of the players in the Walker Motorsport program were identified, Ribbs was convinced he had the right team to take a shot at making the 1991 Indy 500.

“Derrick had Tim Wardrop,” he said. “Wardrop is, to me, one of the greatest engineers that ever stepped foot in Indy. I knew Wardrop, how badass he was. He looked like Ringo Starr with those glasses he wore. Walker had John Waters, he had Buddy Lindblom; he had some great people working for him.”

Wardrop, who came to IndyCar racing from Formula 1, earned a reputation as one of the most creative engineers in the paddock. With a résumé filled with wins, and time spent working with some of the best drivers and teams on both sides of the Atlantic, Wardrop’s credentials were incredibly solid.

His views on race, however, were probed when Walker inquired about his availability for Indy.

“Derrick Walker called me in England and said he had a potential deal with a driver called Willy T. Ribbs and did I have a problem working with a colored driver,” the late Wardrop said. “I was surprised he would ask me that question and I quizzically asked why he thought that should be a problem for me…”

While Wardrop had few things to say about Walker that were positive, he and Ribbs bonded the moment they met. 20 years later, they speak to each other at least once a day. (Wardrop died in 2012, the year after this was originally written.)

THE NEXT STEP

With complete confidence in Walker’s team, Ribbs arranged for some face-to-face time with Bill Cosby to discuss how to move the project forward.

“I told Walker, ‘Look, I’m going to get Bill on the phone and see if we can set up a meeting,’” he said. “Two weeks later Derrick Walker and I were in Las Vegas at one o’clock in the morning in Bill Cosby’s dressing room after a show. I called Bill and said, ‘Derrick Walker is available and he’s won the Indy 500 with Penske, let’s go for it. So Cosby says, ‘Okay. I want you in Vegas in two weeks. And tell him not to wear a kilt!’ because he knew Walker was Scottish… Typical Cosby.”

According to Ribbs, the bond between Cosby and Walker was instantaneous.

“So we met with Bill in his dressing room and Bill loved Derrick,” Ribbs continued. “Fell in love with him. And he says to Derrick, ‘How much money do we need to do the 500?’ And Derrick told him. So we were in the dressing room, oh God, we were in there till three o’clock in the morning. So when the meeting was over, Derrick left back to Pennsylvania, I went back to California the next day. And in two days, Derrick had his money. TWO DAYS! That’s the kind of man Bill Cosby is. On a handshake. No agents, no managers, no lawyers. On a handshake.

“Derrick calls me up on the phone and he says, ‘I don’t believe it.’ I said, ‘What’s the matter?’ He said, ‘Bill already sent the money.’ I said, ‘That’s who he is.’ I mean, Derrick Walker had been getting commitments from plenty of people over the years that never paid him. What Bill wanted to show Derrick Walker was that Willy T. Ribbs and Bill Cosby were straight-up people. That was the message. So it wasn’t a lot of money that Bill sent him, but it was more than enough to get the job done.”

At the time—before Ribbs and Walker Motorsport embarked on their Indy 500 quest—that statement was correct. As they’d soon learn, every ounce of patience and funding they had would be consumed at Indy, and long before they made their first qualifying attempt.

DÉJÀ VU?

With Cosby’s money in the bank, and all of the necessary support equipment to run an Indy 500 program for Ribbs, the final piece of the puzzle was to find a suitable chassis and engine. Walker worked a deal with Euromotorsport to secure a year-old Lola chassis with a reliable but aged Cosworth DFS engine. Walker would pay for the car in installments—as money came in throughout the year—to help lessen the financial burden for Indy.

Ribbs found himself with in interesting dilemma: In 1985, he had a solid budget and the latest and greatest equipment, but lacked the personnel to make the show. For 1991, he faced the opposite problem as Walker Motorsport was loaded with talent, but had a very limited budget, a questionable car, and a past-its-prime engine.

Finding the speed to make the show was the new obstacle to overcome.

“The car came from [Euromotorsport owner] Antonio Ferrari…it was a terrible car…it was a junker,” Walker admitted. “It was an out-of-date car because Antonio had sold me this junk heap and took all the good, updated stuff off it. And the Cosworth engine was just as bad, really old. But you know, you’ve got to have money to get the good stuff. We were just dumb and happy to have the wheels for the car.

“So we loaded up the car and off we went to Indy. And we came here, did the rookie test and we realized that we were way off the pace. Willy needed a lot more time, and we didn’t have much of a competitive car.”

Walker’s team took to the track for the April 26-28 ROP program, but for Ribbs, the results weren’t much better than what he encountered six years earlier.

With every rookie required to complete four 10-lap runs at greater increments of speed, passing ROP requires both speed and consistency. Rain and engine issues prevented Ribbs from completing the four mandatory phases, but with 101 laps under his belt and a best speed of 201.342 in the books, the team came away from ROP with some valuable data to draw from.

The team’s goal of trying to coax more life and speed from the Cosworth DFS was immediately abandoned, and as Walker describes, the only remedy to get Ribbs through ROP and into the race was more horsepower.

“It was obvious right away at ROP,” he added. “We were in trouble. And so we decided while we’re at the test that the thing to do would be to look at getting a Buick [engine]. A Buick, having a lot more power, would probably get us a chance to get in the race. So that’s how it all started. You’d like to think you were so smart and you planned this whole lot out from the beginning…”

Buick’s big, heavy, turbocharged stock-block V6 engine was tops in horsepower, which solved that problem for the team, but it also had a propensity for failure. If the Buick would hold together–which was a 50/50 scenario at that time–a driver could be competitive, but the Chevrolet engine was the prize to have in 1991.

For a start-up team like Walker’s, gaining access to the limited supply of Chevrolets was impossible, which made his next move little more than a formality as the start of official practice for the Indy 500 approached.

“We went back to Pennsylvania,” Walker continued, “rebuilt the car, and I did the deal on the telephone to get a Buick from Vince Granatelli. We built the car up as far as we could, put it back in our truck and went back to Indy for the first week of that month of May, only we didn’t go on the track. We went to Jackie Howerton’s shop on Gasoline Alley and converted the car to Buick power. And the second week we rolled out this car with a Buick in it and started running.”

Walker Motorsport missed the first five days of official practice for the 75th running of the Indy 500, and despite the problems encountered during ROP, and the amount of practice time that was lost, Ribbs says he wasn’t having any flashbacks from his ill-fated 1985 appearance.

“There was no feeling of déjà vu,” he noted. “The Sherman Armstrong/Paul Leffler deal was not even in my mind. I knew Derrick Walker, knew what he could do. And I know he wanted to do it. That was number one. I knew he wanted to make it happen. I knew Tim Wardrop wanted it to happen. So when they said, ‘Okay, look, with the money we’ve got we don’t have the best [equipment], but we’re going back with a Buick to get your ROP done and we’re going to be smart about it,’ I didn’t doubt it.”

AT LEAST IT’S NOT THE STROKER ACE CHICKEN SUIT

A somewhat comical moment came when Ribbs saw his Lola for the first time with its new engine. He’d turned his first laps in the ex-Euromotorsport car carrying the paint scheme that came with the car—a fairly simple red and white affair—but the Lola-Buick, in its new Walker Motorsport paint scheme livery, was rather hideous.

“When you start your own team like this, there’s a lot of things you haven’t really thought about,” Walker said. “We didn’t even have a logo to start. I had a friend of mine helping me a lot, a guy called Pat Wall. He was doing a little bit of design for me, like color schemes and stuff to try and figure out what we’re going to do with the car color. I was keen on having something really noticeable. And so I’d never even heard of the word chartreuse before or whatever the hell they call it. And so we had this, I called it yellow and pink, but it’s yellow and cherry-reddish color.

“So we painted it in these two colors and, of course, Willy, when he saw the color of the car, he was not impressed. That was like asking him to go round wearing a girl’s hat… He was so funny in his condemnation of the car color. But I really wanted to have a color that people would pick us out because we certainly had no [sponsorship] logos on it. And so we needed to showcase it. I was happy to say that we did get noticed, and Willy probably to this day, still thinks the colors stink.”

Walker must be a mind reader because Ribbs’ is still hot over how bad the car looked.

“Well, I swear he’s right,” Ribbs said. “Pat [Wall] and his brilliant idea, which I didn’t think was too brilliant, decided, well, let’s paint it where everyone can see it from 20 miles away. Yeah, that was it. Well, shit, even at 20 miles it was damn ugly… And the next thing I know they rolled this thing out of the trailer painted like that. I thought, hell, man…Willy T. Ribbs is already questionable, okay? You’re going to make it even harder for me driving around with stuff like this? I was pissed. I mean, shit, paint it red or black or blue…I already standout. I said, ‘What the fuck, Pat?’ I’m already a marked man…I’m already cake, don’t put the icing on it.’”

To make matters worse, Wall’s appalling looks-like-a-Muppet-exploded livery was actually voted as having the “Best use of color and design” by series sponsor and paint manufacturer PPG at the year-end CART banquet. The check for $10,000 that came with the award, however, was greatly appreciated by Walker.

Ribbs’ disdain for the chartreuse yellow is understandable, but when it comes to the Lola’s use of hot pink…it should be noted that the driver in question wore a helmet for many years adorned with a very similar color…

NEXT: Ribbs gets ready to qualify