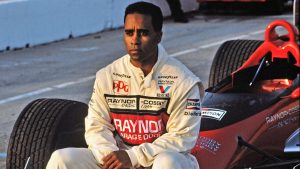

In 2011, The Indianapolis Motor Speedway celebrated the 20th anniversary of Willy T. Ribbs’ breakthrough performance to become the first African-American to race at the Indy 500. I wrote a five-part feature to honor the historic event for FOX’s former SPEED.com site in 2011, and 2016 marked the moment’s silver anniversary, which made repurposing the feature a worthwhile effort.

Ribbs’ journey to make the field for the 1991 Indianapolis 500 was filled with defeat, elation, bitter disappointment and immense pride. In terms of reaching the human limit for emotions, Ribbs experienced wicked highs, lows and everything in-between.

His tale, as much as it’s centered on race, is also universal. The story of a talented athlete who must overcome staggering odds to succeed is a staple in Hollywood, and for Ribbs, his time in open-wheel racing read like a movie script from the outset.

*In the years that followed the original publishing, a key character in the story, comedian and actor Bill Cosby, was accused of multiple rapes, tried, convicted, and sentenced to prison. Please proceed with the understanding that Ribbs’ story is impossible to tell without Cosby’s inclusion. He was released in 2021.

Originally posted in May, 2011.

PREAMBLE: THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN BEING FIRST AND BREAKING BARRIERS

“There were people that came before Willy and you have to give that history,” Bill Cosby said in a polite but insistent tone during a call from his home in New York.

Cosby, who sponsored Ribbs from 1990-1994, spoke at length and with great pride about his involvement with the renowned driver, but also made a strong point regarding Ribbs’ historical placement from the outset of the conversation.

Ribbs, who will forever be known for what he accomplished at Indy in 1991, is often—and inaccurately—credited for breaking American auto racing’s color barrier. That distinction, which Ribbs happily admits, belongs to others from the 1920s, and also includes his hero, Joie Ray.

It’s undeniable that Ribbs was the first African-American to race at the Indy 500, but the barriers that once prevented drivers of color from racing at the fabled Speedway were broken down over time by men like Ray and Ray’s predecessors, those who raced in the popular Gold and Glory Sweepstakes open-wheel circuit, sanctioned by and held for African-American drivers while Jim Crow policies were practiced in the Midwest.

Ray, often referred to as the “Jackie Robinson of auto racing,” received the first competition license awarded to a driver of color by the American Automobile Association—AAA—in 1947, a week prior to Robinson’s Major League Baseball debut for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Although his name is missing from the annals of the Indy 500, Ray came close to participating in the 1950s, and his impact, like the ones made by his fellow Gold and Glory racers—men named Mel Leighton, Charlie Wiggins, Leon Warren, Sumner Oliver, Jack Desoto, Bill Jeffries, Charles Stewart and many others—paved a direct path that eventually delivered Ribbs to Indianapolis.

The doors to the Speedway weren’t always open to the trailblazers that came before him—but as Cosby rightly proclaimed, it was their strength of character and perseverance that helped Ribbs to complete the work they started.

PRELUDE TO A DREAM?

While Ribbs is most closely associated with the 1991 Indy 500, his history with the Speedway actually began six years earlier.

Just three years removed from his last open-wheel appearance in the Formula Atlantic training series, Ribbs took the SCCA Trans-Am series by storm from 1983 to 1985, winning 14 times and establishing himself as the hottest property in sports car racing.

With his stock on the rise, and through an odd introduction to a famous promoter in 1984, Ribbs began to craft a return to his open-wheel roots and set his sights on the 1985 Indianapolis 500.

Had that first Indy 500 encounter worked out differently, it could have been the year where Ribbs was reclaimed by open-wheel racing. As it unfolded, Ribbs would quickly return to sports cars. It took six years for the bitter memories of 1985 to wear off.

“In ’84 I was racing in Caesar’s Palace at the Trans-Am race for Jack Roush,” Ribbs said. “I think I had a flat tire – I had to make a pit stop. I didn’t have a great finish because I had to catch back up, but it was a dramatic comeback drive. After the race, this black guy came up to me and he says, ‘Don King would like to meet you.’

“I knew Don King was in town because there was a fight between Larry Holmes and Bonecrusher Smith at the Riviera. I said, ‘Okay,’ and he says, ‘He would like you to be a guest at his fight but he would first like to meet you for business.’ So I said, ‘Okay.’ I said, ‘When?’ He says, ‘Tonight.’”

Ribbs didn’t know it at the time, but his upcoming meeting with King would change his life—for better and for worse.

“So I went to his office that evening and he told me about what he thought he could do and what I was doing was really different and special and ‘another Jackie Robinson’ kind of thing,” Ribbs said. “He said he’d like to help me. I said, ‘Great.’ So he said, ‘I want you to go to the fight tonight. Here are some tickets.’

“So I went to the fight and was really on a high. And then the next week he was on the phone and we sort of worked out a deal where he was going to be promoter and manager but it took six months to do the deal because…the people who he was used to representing, fighters, could not read or write.”

Among Ribbs’ greatest attributes is his intelligence which, the native of San Jose, California, says was not welcomed by King.

“So when I got the first contract from Don, I X’ed out nearly every page and sent it back to him, and his lawyer didn’t like that!” Ribbs continued. “I told Don, I said, ‘Look, those fighters that you represent don’t come from a family like mine.’ And I said, ‘I hate to be arrogant, but my family is business-oriented, with a business that was started in 1927 by Henry Ribbs, my grandfather. So, Don, you’re dealing with a different person than your fighters who’ll sign anything you put in front of ‘em.’

YOU’VE PICKED THE WRONG SPORT TO MAKE MILLIONS

Ribbs continued to fight for what he felt was a fair and equitable contract, but he says the differences in attitudes and finances between boxing and Indy car racing never registered with King and his associates.

“There was a lot of heckling and ‘M F’s’ thrown at me…especially from his lawyer, a black cat named Charlie Lomax,” Ribbs said. “This dude, with his hair slicked back, kept telling Don that I was being controlled by white people. Oh yeah, it was funny as hell!

“And so after six months we finally got a deal done and the deal was done on the contract that my lawyer gave back to them. Finally they gave in and Lomax and Don said, ‘All right we’ll do it.’ It all centered around an open-ended expense account for Don. Big. Very big.

“If Don went out and did deals for me, he wanted unlimited expenses for him to do the deal. And I said, ‘Look, Don, come on. You spend more on expenses for one fight than we do to run a car for the year. That ain’t going to happen, so you can forget it.’ It was all about profit for them, but they finally gave in.”

THIS KIND OF CROW DON’T FLY

With King looking after his career, Ribbs soon had the funding to enter the 1985 Indy 500. But no amount of money would be able to overcome the ideological differences that emerged between Ribbs and some members of his Indy car team.

“We got the deal done and Don called a friend of his at Miller Brewing Company and said, ‘Why don’t you sponsor Willy Ribbs for the 1985 Indy 500?” Ribbs said. “Don had already had a relationship with them. When Don got the money, phone calls came into him from a lot of different [team owners], and one came from Sherman Armstrong, who said ‘I can do the deal.’”

Armstrong, a veteran Indy 500 entrant who had a modicum of success at the event, offered King a team for Ribbs that looked like a winning proposition—at least on paper.

“Well, I liked Sherman Armstrong, he was a good person but wasn’t too involved, you know?” Ribbs explained. “Sherman owned the team and [7-time Indy 500-winning crew chief] George Bignotti was sort of the figurehead. So they put up the money and, you know what? I was naïve. It sounded great, but I was naïve.”

Ribbs rarely mentioned race or racism in more than three hours of conversations, but that changed when he described Armstrong’s chief mechanic.

“Paul Leffler was the crew chief, my head mechanic,” he said. “He was the biggest racist I’d met in my life, biggest racist I’d ever met in the sport of auto racing. I had never met anybody like him before or after. And he made it clear to me that he was not interested in me being in the Indy 500 even though he was getting paid by Sherman Armstrong to get me there. Bignotti was the big name who was attached to the team, but George wasn’t the guy who was putting the car together, who was controlling what happened on the car. That was Paul Leffler.”

With don King’s backing, Armstrong entered a new March-Cosworth for Ribbs in 1985–a highly competitive package at the time. The chassis/engine combination won Indy in 1983, 1984, and again in 1985, which meant getting up to speed and passing the mandatory Rookie Orientation Program (ROP) should have been little more than a formality.

But Ribbs—a driver whose speed and bravado had never been questioned before his arrival at Indy —failed to get past the first of four speed phases and quickly withdrew from the event. For Ribbs, who expected so much from his first trip to Indy, it was a humbling experience.

A LITTLE PIECE OF PLASTIC

The circumstances behind Ribbs’ failure in 1985 can be attributed to one item: The lack of a certain component that made driving the car all but impossible.

Rather than set the car up to go slow, or in such a way that would risk hurting the car or driver with a crash, Ribbs says his chief mechanic quietly created a scenario where failure would fall squarely on his shoulders. To the average onlooker, Ribbs would be unable to muster the speed—and the courage—to earn his rookie stripes.

“I was sitting up pretty high in the car to begin with, and for whatever reason, they didn’t install the windscreen—that clear plastic air deflector piece—to make the air go over the cockpit,” Ribbs said. “I went out and was trying to run without it, but the air was damn near trying to pull my head off every lap. My head was bobbing around the cockpit the whole time. There was nothing I could do about it. Being half-blind and shaking all around is a hell of a way to try and learn your way around Indianapolis.”

Picture Ribbs shaking his head left and right as fast as possible—as if he were saying ‘no’—while traveling at upwards of 200 mph on Indy’s long straights. The violent aerodynamic forces whipping his helmet side to side on a potentially lethal track like Indianapolis made judging when and where to turn the car an impossible situation that bravado could not solve. Minus the windscreen, the one direction he needed to look—ahead—was not an option, which led to a dire lack of speed during ROP.

When a windscreen did appear, it was cut down, leaving Ribbs’ helmet mostly exposed. Compared to the screen on Rahal’s car (above), the No. 43’s screen wasn’t particularly effective.

Ribbs ran 48 laps with a best of 172.2 mph, and compared to the two fastest rookies that day—Ed Pimm at 199.0 mph and Arie Luyendyk at 195.5 mph—he was well off the pace. Why the windscreen wasn’t made available or installed is unknown, but for Ribbs, the team’s choice to withhold that vital component was the first indicator that things were headed in a wrong and highly dangerous direction.

“After one day of running, I knew it wasn’t going to work and I got several phone calls from some very powerful people that were involved with me that said, ‘Get out of the car,’” Ribbs said. “And I did just that. One of the calls was from a personal sponsor of mine. They’d heard from people that what went down was only the beginning. I was there with my best intentions, but the relationship with Paul Leffler was zero, and so I got out of the car. And the media tried to crucify me, calling me chicken. They tried to rip my guts out and I’ll never forget them for it. I remember who they were by name. So that’s what happened in ’85. And if you want to ask about Paul Leffler, call [IndyCar reporter] Robin Miller. He was there.”

While Miller’s interactions with Leffler had nothing to do with race, he wasn’t surprised to hear Ribbs’ account of how the two struggled to work together. He also recalls witnessing the problems Ribbs encountered with the car.

“The thing about Leffler,” Miller said, “was that he was a hardcore USAC Sprint car guy. And I’m sure he wasn’t wild about some guy he didn’t know driving this car… I remember the car really didn’t have much windshield, so it probably scared the shit out of Willy on the short chutes and beat the hell out of him going down the straightaways, because that’s what the wind did to you without it.”

DOCUMENTING THE DAY

Miller wrote a story about how Ribbs’ introduction to Indy played out, and recalls the questionable circumstances that led to his struggles. To his credit, Ribbs kept the intra-team drama to himself and accepted the blame for the poor showing.

“I remember doing a column right after [ROP], just saying that it was unfortunate,” Miller added. “The whole circumstance just didn’t work out because it was almost like he was sabotaged. Here you go. April 27th, 1985, Indianapolis Star:

“Ribbs Withdraws From Indy 500 Field: Willy T. Ribbs made history Saturday at the Speedway. Then he made a tough decision, becoming the first black driver to ever circle the Speedway. Even more, Ribbs said he came to the conclusion he wasn’t ready for 200 miles an hour. ‘I didn’t feel comfortable so I thought it was best for everyone if I wait and race at the Meadowlands in June,’ said Ribbs during a hastily assembled press conference Saturday. ‘I’m disappointed but I just need more time to prepare myself.’ Ribbs had never been on an oval or in an IndyCar before Saturday morning. He made some 50 laps in his Miller Beer March 85C during the second day of USAC’s rookie orientation session. His top speed was 170, and the twenty-nine year-old road racer said it wasn’t much fun. ‘The car was so new, the windshield wasn’t even all the way up, I couldn’t even hold my head still going down the straightaway,’ explained Ribbs, who has excelled in the Trans-Am series the past two years.

“‘Everything was a blur and I couldn’t see the corners clearly. You can get hurt here if the car doesn’t feel right. I knew that it would take more than two or three days to reach competitive speeds and I don’t want to look like a fool and get in somebody’s way.’ Ribbs was asked the question of being scared. ‘It’s a matter of good common sense, not fear. Some guys might’ve kept going and pushed themselves and ended up in the wall. Wasn’t easy, it was just tough.’

“George Bignotti, who was slated to be Willy chief mechanic, applauded the withdrawal. ‘It takes quite a person to say he’s not ready for this place,’ said Bignotti, ‘it’s a big transition from Trans-Am to Indy cars and he wants to come back here next year when he’s got some miles under his belt. All I’ve got is praise for Willy.’ Sherman Armstrong, in the deal which came together late last week, agreed. ‘To say Willy chickened out is very darn unfair. I think it took more courage to make this announcement tonight than it did for him to go around the track. We’re going to run in Meadowlands and maybe an oval race.’”

TIME DOESN’T HEAL ALL WOUNDS

Not only did the run at the Meadowlands never happen, it took Ribbs until 1990 before his open-wheel aspirations were met with a better opportunity. He walked away from Indy in 1985 feeling like he’d been cheated, was unwanted, and even worse, that his talent and manhood had been called into question.

“At the time, I didn’t want to be the rookie who got into the press conference and blamed his team,” he said. “A lot of what I said was true. I did need more time, but I felt we could get me through ROP and I could keep learning. Yeah, it was a tough place. But it’s not like I couldn’t cut it. Like I said, I was naïve. With a different team, I could have made it through ROP; there’s no doubt in my mind. But I wouldn’t get that chance if I told the truth back then so I kept my mouth shut and swallowed my pride.”

Ribbs’ was left seething after his Indy 500 dreams were put on hold, and for a man with such a competitive nature, the most frustrating aspect of the experience came from knowing he wasn’t given a fair shot.

With a new car at his disposal and famous name like Bignotti involved in the program, Ribbs’ reputation also took a beating after washing out from ROP—something that only happened to the most circumspect drivers.

Although his career in sports car was waiting to be resumed after the encounter with Armstrong’s team, Indy 1985 took a quite a toll on Ribbs’ spirit. To this day, some of those who worked with him at Indy in 1991 question whether he was ever able to move past those painful memories of Leffler and the media scrutiny he faced.

One thing is for sure: Indy 1985 didn’t sit well with him. Ribbs was left to stew and plot and fight for the rest of the decade as he wondered if he’d get a second chance to prove himself at the crucible of speed.

Getting back to Indy—to honor his heroes and to write his name in the history books—was about to become an obsession for Willy T. Ribbs.

NEXT: Enter Cosby